Schizophrenia and Language

The language that we use to describe schizophrenia and the people suffering from it is one of the most hotly contested debates in the field of mental health in the UK today and engenders some very intense emotions on all sides. I have personally witnessed people walking out of meetings because a term that they disapproved of was used by one of the other people attending.

Clearly, in a society that so often skilfully uses language to demonise or demean people with schizophrenia we should pay this issue particular attention but on the other hand we need to recognise that this debate has often in the past been used to promote alternative views of schizophrenia that do not fit with the personal experiences of sufferers or carers and so we must be cautious of adopting new terminology without first giving it careful thought. There is then a clear challenge that in seeking to outlaw the use of clearly perjorative terms like “bonkers” and “psycho” we do not end up shooting ourselves in the foot by helping to minimise the very real suffering that an illness like schizophrenia causes.

It is also important that we, as this group of people living with schizophrenia, have a clear view of what schizophrenia really is. We know for instance that schizophrenia is a very serious condition and that it often causes disturbed behaviour but other aspects of it are not as sharply defined. For instance people who have recovered well from a first episode may look on their schizophrenia as an illness that they suffered from once but are now cured of whereas someone who has had repeated episodes may regard it as more akin to a disability which they will carry with them for the remainder of their life. With differing experiences of the condition will inevitably come different definitions and our language must be able to take this into account.

We must also be aware that at different times different terminology will be in vogue and this is part and parcel of the normal development of language. In his 2003 book, The Blank Slate, Stephen Pinker1 coined the term the “euphemism treadmill” to describe the process whereby new terms that are considered less offensive are introduced only then to be thought to be offensive themselves after the passage of time. Thus it was that the term “patient” replaced “lunatic” in the mental health system in the middle of the 20th century only then itself to be replaced with “service-user “ in the 21st century.

The British Media and the Language of Schizophrenia

Traditionally the press both lead and reflect public opinion in the UK so they are important opinion-formers. (Image: Mitrija on Shutterstock)

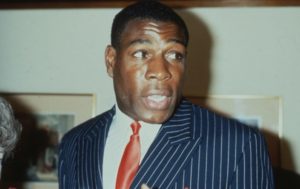

It has been a traditional role of the British news media to both lead and reflect public opinion and without a doubt what the public thinks and believes about schizophrenia is very much conditioned by what they read and hear in the news. There is no doubt that in sections of the British news media there is at best a poor understanding of the terms applied to people with mental illness and at worst a deliberate attempt to smear those people by the use of inflammatory and rancorous language. Sometimes the headlines are seen by the public to be outrageous as in the case of The Sun’s infamous September 2003 front page headline “Bonkers Bruno Locked Up” a story about the boxer Frank Bruno’s mental illness.2

It is true that the Sun, in the face of clamorous public opposition to this, back-tracked very quickly and made a donation to a mental health charity in reparation but nevertheless I have personally heard editors of national newspapers quite openly justify their use of terms like “psycho” to describe people with schizophrenia. I have also seen papers such as the Daily Mail describe a person with schizophrenia who had killed as “evil”. Such provocative language may help them to sell newspapers but it does nothing to help alleviate the very real problem of dangerous behaviour that people with schizophrenia face in the UK today.

Although quick to report on the instances of violence by people with schizophrenia the much greater number of suicides often go unreported. (Image: Photographee.eu on Shutterstock)

And it is on this issue of reporting dangerous behaviour by the press that serious questions arise. Because whilst the press will report in great detail on every incidence of violence by people with schizophrenia only a tiny fraction of the thousand suicides by people with schizophrenia in the UK each year are reported at all and very few of them make it to the national press. This disparity in reporting is not accidental. It is important to some sections of the media to be able to demonise people with schizophrenia and the reality that people with schizophrenia are more often than not victims of their own dangerous behaviour is an inconvenient truth. In general press reports that focus on violence by people with serious mental illness outnumber sympathetic reports by about four to one.7

There has been some opposition to the use in the media of the term “schizophrenic” as a noun to describe a person with schizophrenia. This is commonly done in the UK media. The BBC has recently defended its use of this term by comparing it with other terms such as “diabetic” which would not be considered controversial.3 Opponents of this term feel that its use defines people with schizophrenia solely in terms of their diagnosis and ignores all their other qualities and features. Maybe they have a point but maybe we should also ask whether we really need to be attacking terms like this when the real battle we need to have is with those sections of the press who use really offensive terms like “psycho”. Until that battle is done, it seems to me, having a debate around “schizophrenic” will just be a distraction.

British boxer Frank Bruno whose mental breakdown was so poorly reported by the press. (Photo: David Fowler on Shutterstock)

But where media reporting is concerned it is as much about what is left unsaid as the terms that the media use. I have yet to see a story about a violent incident involving schizophrenia that gives any background information about the condition to put the act into context. For instance what schizophrenia is, what causes it and how many people are affected. And there is rarely any discussion about the factors that exacerbate the condition and make dangerous behaviour more likely: factors like the desperate under-funding of the Mental Health Service: another inconvenient truth. Violent acts tend to be presented by the media as criminal in intent when clearly no crime can have been committed if the perpetrator lacked the mental capacity necessary to form any intent.

Should Language be an Issue at All?

Is it right in the first place for people to make demands on society to use particular language? Well perhaps that depends on who is making the demand. Perhaps it could be argued that we, as people living with schizophrenia who are often the focus of the stigma that society creates partly by its use of language are not only entitled to make such demands on society but also are the people best placed to make those demands.

And after all if we do not make such demands on our society then what next? There are no bodies policing the use of language and in the absence of clear guidance from government, who do not seem to have much to say on this issue, somebody must steer the nation towards a set of terms that can be used without giving offence and which will contribute to progress on mental health issues.

It is often claimed by mental health charities that the stigma faced by people with mental illness is as bad as the illness itself. This belief has its roots in the anti-psychiatry movement that was so influential in the mental health field in the second half of the 20th century. Whilst I can’t speak for any other condition, I have enough experience of schizophrenia to challenge this assertion. Many people with schizophrenia will endure a life-changing illness that will probably be the worst thing that has ever happened to them and will be a terrifying and deeply cruel experience. It is unlikely that they will meet any stigma after becoming ill that will in any way match the suffering that they have endured at the hands of their illness. It is vital that the language that we use in describing this condition reflects the enormous impact that it has on people’s lives.

Getting the Basics Right: Accuracy

Sadly, the UK media still often confuse the terms psychotic and psychopathic. (Image: Feng Yu on Shutterstock)

Perhaps the first and most obvious demand that we can make of our society when it comes to the language used to describe mental health is simply, accuracy. For instance the term schizophrenic is used far too loosely by some: it is simply not accurate to describe as schizophrenic someone who holds two conflicting views on an issue, nor is it accurate to confuse the terms psychotic and psychopathic and it is definitely not accurate to describe someone who commits a crime because of their schizophrenia as “evil” because they patently do not have the mental capacity to hold any evil intent.

Schizophrenia is one of the most misunderstood public health issues in our society. The erroneous belief that schizophrenia means a split personality endures today even after many years of “awareness-raising” work by the mental health charities and the association between schizophrenia and violence is still one held by most people. It is precisely because schizophrenia is so poorly understood in our society that we must demand a basic level of accuracy in reporting and in the use of terms.

After all this is not such a controversial demand to make. IPSO, The body set up to oversee and police reporting by the press clearly requires in its Editor’s Code of Practice that “the press must take care not to publish inaccurate, misleading or distorted information”.4 And as far as the broadcast news is concerned the Ofcom Rules on accuracy are equally explicit and require that “News, in whatever form, must be reported with due accuracy and presented with due impartiality”.5

What Language Should We Use?

Patient, Client or Service –User?

What we call people suffering from schizophrenia is perhaps one of the most popular debates in this issue of language. In a recent focus group consisting of people with a diagnosis of serious mental illness that I was a member of, run on behalf of the Department of Health, one of the questions that we were asked was what term would we best use to describe ourselves and we looked at a number of options: “patient”, “client” and “service-user”. I was surprised to find that none of we service-users actually liked the term “service-user” and we questioned who had first thought it up. We thought that it was clumsy and presented us as being people who consumed services whilst not contributing anything in return.

In the end we thought that “client” was by far the best term as it described the paying relationship that we have with the health service. After all we pay for our health services every time we pay our National Insurance contributions and income tax and for those who are not working they pay every time they contribute their 20% VAT when they buy something in the shops. The term “client” also implies that our health care is a right not simply something that is bestowed upon us by a beneficent society or by well meaning nurses and doctors.

This unanimous dissatisfaction in that group with the term “service-user”, which is currently in very common use and has been enthusiastically promoted by the mental health charities, was surprising but not unexpected. The adoption of the term in the first place was another example of the “euphemism treadmill” and was a reaction to the use of “patient” which had become thought of as perjorative.

Mental Illness, Emotional Distress or Mental Health Problems?

If we have a choice in the terms used to describe people with schizophrenia we have considerably more choice in describing the condition itself. “Mental illness”, “mental distress”, “emotional distress”, “spiritual distress”, “mental health problems” and “mental health issues” are all in current usage in the mental health field in the UK. Some of these terms are genuine attempts to find a more neutral and less perjorative description however others are just blatant attempts to re-define schizophrenia as something which it is not: to deny that schizophrenia is the severe, disabling and life threatening condition which it so often is. After all isn’t describing schizophrenia as a “mental health problem” a bit like describing lung cancer as a “chest problem” and we would not do that?

It is vital that whatever term we use to describe schizophrenia, the seriousness of the condition comes across clearly in that description and is in no way minimised. If we attempt to minimise the impact of schizophrenia on the lives of those living with it then we risk denying ourselves access to the services and treatments that are essential to a successful recovery and (once again I say) are our right. And vitally we deny ourselves the right to that commodity that in the case of schizophrenia is so often in such short supply in our society: I mean sympathy.

It is also vitally important that whatever terms we use, we do nothing to imply that people with schizophrenia are to blame for their actions. People with schizophrenia whose stories end up in the papers are usually there because at some time in their illness they have lost the mental capacity to make their own good judgements and their disturbed thinking has led to equally disturbed behaviour. This is not their fault; it is simply another cruel feature of this illness. It is important that the terms that we use adequately convey this and whereas “mental illness” goes some way to achieving this “emotional distress” certainly does not.

The use of language is vital to people with schizophrenia. So often language is used to belittle or demonise us and is essential to society’s misunderstanding of this complex condition. Schizophrenia is very often one of those subjects that society feels deeply uncomfortable discussing until that is something goes wrong. However if we are to move society forward in the care and treatment of people living with schizophrenia we must not only encourage a more open debate around this subject but we must also carefully consider the language that we use in that discussion.

References

1. Pinker Stephen, 2002, The Blank Slate: The Modern Denial of Human Nature, Penguin Press Science.

2. Sun on the Ropes Over Bonkers Bruno Story, reported in the Guardian, 23/09/2003.

3. Time to Change website, http://www.time-to-change.org.uk/news-media accessed 16/12/2015.

4. Independent Press Standards Organisation website, https://www.ipso.co.uk/IPSO/, accessed 16/12/ 2015.

5. Ofcom website, http://www.ofcom.org.uk/, accessed 16/12/2015.

6. Unless otherwise referenced the content of this information sheet is based on the author’s personal experiences.

7. Philo G, 1994, Media Images and Popular Beliefs, published in Psychiatric Bulletin.

Copyright © January 2016 LWS (UK) CIC.