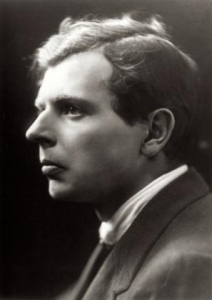

Ivor Gurney

Ivor Gurney. (Image: Richard Hall, Ivor Gurney Estate/Gloucestershire Archives)

Ivor Bertie Gurney was one of England’s greatest war poets of the Great War and a renowned composer described by some as an “English Schubert”. He loved Gloucestershire, and the Gloucestershire countryside and his war experiences were to form the two major influences on his creative output. He also suffered from serious mental illness throughout his adult life and which ultimately resulted in his confinement in one of the large mental asylums so common in those days. Some scholars have suggested that Gurney suffered with schizophrenia whilst others have argued that bipolar disorder would be a closer diagnosis. However from the contemporary descriptions of his symptoms it is clear that his troubles lay somewhere on the psychotic spectrum.

Gurney was born in Gloucester, England on 28th August 1890, the eldest son of David, a tailor by trade and Florence a seamstress. He was christened Ivor Bertie after one of his father’s important clients.

At age eight Gurney became a chorister at All Saints Church in Gloucester and in 1900 joined the choir of Gloucester Cathedral. He was educated at the Kings School, Gloucester. In 1906 he became an assistant organist at the cathedral and in 1911 won an open scholarship to the prestigious Royal College of Music in London where he was to be taught by Sir Charles Villiers Stanford, one of the greatest English musicians of the day.

Whilst at the R.C.M. Gurney met and formed a very close friendship with Marion Scott; a relationship that was to survive his later confinement and endure until his death. Scott acted for many years as his agent and ensured that his works were submitted for publication when he was unable to do so.

During his early days the mental clouds that were to dominate Gurney’s later life began to gather and he suffered from episodes of deep depression interspersed with periods of exuberance and at points came very close to experiencing a complete breakdown. Although his creative output was prodigious he was not skilled at making money from his calling and at times he experienced serious poverty.

The First World War interrupted Gurney’s musical studies and in 1914 Gurney volunteered for military service with the 1/5th Glosters but was initially rejected on account of his poor eyesight. The following year at age 24 years and 6 months he tried again and was accepted into the 2/5th Glosters with the rank of private. He was first sent to the Gloucestershire Regiment depot for basic training followed by combat training near Northampton, England before being sent to France.

Gurney’s previous mental ill health appeared to go into remission during his time in the army. Later his siblings and childhood friends would describe him as a loner and an odd-man-out in his early years and it is possible that in the army he experienced a sense of camaraderie under conditions of shared suffering that he had not previously known and which he found very beneficial.

However, during his time in the trenches Gurney suffered a severe psychological blow when his best and closest friend from before the war, the poet Will Harvey, with whom he had enlisted, was sent on a solitary reconnaissance mission into no man’s land and did not return. Harvey was listed as “missing presumed dead” and Gurney was deeply moved by his lost. However Harvey was not harmed: he had been captured by the enemy and was held for two and half years in German prisoner of war camps. Following this trauma Gurney wrote one of his finest poems: “To his Love”.

He’s gone and all our plans

Are useless indeed.

We’ll walk no more on Cotswold

Where the sheep feed

Quietly and take no heed.

You would not know him now….

But still he died

Nobly, so cover him over

With violets of pride

Purple from Severn side

Gurney saw action at Ypres, The Somme, Paschendale and Arras. In April 1917 he was shot in the arm during the Battle of the Somme and then in September of that year was gassed at Paschendale following which he was sent back to the UK for convalescence. He returned to training in November 1917 but suffered greatly with his old problem of depression. In February of 1918 he was returned to the Lord Derby Military Hospital in Warrington which specialised in mental health, where he was diagnosed with shell shock (what we would today call post traumatic stress disorder)1.

Gurney’s family were by now becoming increasingly disturbed by the rambling content of his letters home and whilst at the Lord Derby Hospital, in June of 1918, Gurney attempted to take his own life but was not successful. He wrote suicide notes to Sir Hubert Parry (a famous English composer and close friend, previously the head of the Royal College of Music where he studied) amongst others in which he shows a considerable insight into his madness and also into the enormous societal stigma that haunted psychotic illness then (as now). “I am committing suicide partly because I am afraid of madness and punishment and partly because my friends would rather know me as dead than mad”2.

Following this attempt he told the medical officers at the hospital that he had been hearing voices telling him to commit suicide and voluntarily asked to be sent to a mental asylum. He was then transferred to the Middlesex War Hospital at Napsbury in Hertfordshire where he stayed for three months.

Gurney was discharged from the army on medical grounds on 4th October 1918 with a war pension of just eight shillings and threepence a week (around 42 pence today). After his war service he took a succession of short-term jobs but found it difficult to hold down lasting employment. In 1919 Gurney returned to composing and the next two years were very productive for him. However his mental health continued to worsen

W.H. Trethowan, in his comprehensive essay of 19813, drawing on interviews with family, friends and the professionals involved in Gurney’s care, gives us an insight into the course of his increasingly worsening psychosis. He heard voices and formed the belief that the police were spying on him and attacking his brain with radio waves. He would sit with a cushion on his head to try to ward these attacks off. (The belief of being controlled technologically by external malevolent forces is typical of schizophrenic illness in the modern world. Today sufferers often complain of being controlled over the internet or of having microchips secretly implanted into their brains).

Gurney also had grandiose delusions, believing at times that he had been responsible for writing some of Shakespeare’s works and of Beethoven’s symphonies. He believed that he was being visited by the great composers and would converse with Beethoven and Bach. His body clock became inverted and he would remain awake at night and sleep during the day. During this time he shared his brother Ronald’s house in Gloucester but he and his wife found Gurney’s activities so disruptive that they could no longer bear it. His behaviour became increasingly disturbed and reached a climax when he approached the local police and asked to borrow a gun with which he intended to commit suicide.

As Gurney’s local paper was later to say about him: “In 1921 the sensitive mind was so far from being able to distinguish between reality and illusion that retreat from the world became necessary”4.

In September 1922 at the instigation of his brother, Gurney was certified as insane and then duly confined in Barnwood House, a mental hospital just outside Gloucester, where he stayed for three months before he escaped during the night and had to be returned by the police. From there he was transferred to the City of London Mental Hospital at Dartford in Kent (also known as Stone House Hospital) on 2nd December 1922 where the initial diagnosis according to W.H. Trethowan was of “systematic delusional insanity”, an old style classification that was synonymous with schizophrenia at the time (it should be remembered that the term schizophrenia had only recently come into common use).

During his confinement Gurney continued to work but his output declined progressively. He also found some measure of relief from his mental struggles by working on the hospital farm a type of work that he had also previously benefited from whilst living in Gloucestershire. Many of the old asylums of that age had an accompanying farm where patients could spend time in useful occupation in agriculture or horticulture and it was often noted by the staff how beneficial such occupation could be on their symptoms. Sadly the asylum farms were closed down in the 1960’s on ideological grounds, to be followed a decade later by the asylums themselves. Stone House escaped the first round of asylum closures and continued as a mental hospital into the 1990s but has now been closed and the buildings are awaiting redevelopment. In his biography, The Ordeal of Ivor Gurney, Michael Hurd gives some deeper insight into his mental state at this time. The Head Nurse, a Mr Fletcher describes him as “a hostile patient but not violent……not troublesome, simply difficult to reach”7. An entry in the Stone House Medical Records is particularly insightful:

“The electricity manifests itself chiefly in thought. Words are conveyed to him. They are often threatening and they have been obscene and sexual. He has heard many kinds of voices. He sees things when he is awake, faces etc that he can recognise”7.

Stone House Hospital. (Image: Glyn Baker from Geograph.org.Uk on Wikimedia Commons)

Gurney was to spend the last 15 years of his life in Stone House. Over time the delusional beliefs that had previously come and gone in episodes became fixed and permanent; a feature characteristic of schizophrenia. Occasionally he would become abusive and violent and his speech disordered.

Whilst still confined in the Dartford hospital Gurney contracted tuberculosis, a chronic infection of the lungs not uncommon at that time but which some have said may have been a long delayed affect of his gassing at Paschendale. This was the time before antibiotics when there were no effective treatments available and consequently Gurney died on Boxing Day 1937. Just as happens in so many cases today, Gurney did not ultimately fall victim to his deluded thinking but rather to the increased risk, which is coincident with the schizophrenic condition, of contracting a physical illness. Still today people with schizophrenia will die between 12 and 20 years earlier than the general population because of their increased risk of physical conditions such as heart disease, stroke or infectious illness.

Many scholars have attributed Gurney’s mental illness to his traumatic experiences in war time but this can be refuted. The hypothesis that adversity, particularly in childhood, can cause schizophrenia to occur later has been around for a long time and has been extensively studied and the great weight of evidence suggests that other factors such as genetics and complications during pregnancy and birth are far more influential. And besides if adversity did cause schizophrenia then we would have expected to see epidemics of schizophrenia following societal traumas such as world wars or the Holocaust but such epidemics have never been observed. This isn’t to say that experiences of adversity are not potentially psychologically damaging; they often are, but simply that they do not cause schizophrenia which is a distinct and discreet condition with its own unique set of characteristics. This issue was clouded somewhat by the propensity of some of Gurney’s friends and followers, out of a sense of sensitivity to his memory, to refer to his earlier shell shock diagnosis as being the cause of his confinement in the mental hospital for some time after he left the army.

Ivor Gurney Memorial Window in Gloucester Cathedral, UK. (Image: Julian P Guffogg and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence.)

Gurney was buried at St Matthew’s Church, Twigworth in Gloucestershire on Sunday December 31st 1937. The service was conducted by Canon Alfred Cheesman, Gurney’s godfather, and fellow composer Herbert Howells played Elgar and Parry on the organ. Present also were representatives of his old regiment, the 2/5th Glosters. As his obituary in the local paper said of him: “His sufferings, mental and physical were to prove beyond healing”5. In addition to the enduring memorial provided by his copious works, a stained glass window to his memory has been installed in Gloucester Cathedral.

During his life Gurney was known as the “Poet of the Severn and the Somme” after his first collection of poetry published in 1917. But it has to be said that recognition came only reluctantly to him: late and slow, and in their obituary The Times newspaper acknowledged that his work was only known at that time to a small circle of poets and musicians6. Some have said that Gurney’s poetry has been eclipsed by the giants of the First World War such as Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon but his memory has endured nonetheless. During his life Gurney produced some 265 songs and 300 poems. But like the great dancer Nijinsky, who’s life we cover in another information sheet, Gurney’s was a life of sadness and a life of what may have been. When the clouds of schizophrenia congealed over his fertile and sensitive mind he was no longer able to produce coherent work and with this knowledge his output gradually declined.

References

1. Ivor Gurney’s Army Record at the Gloucestershire Archives, Gloucester. Viewed on line 5/12/2017.

2. Ivor Gurney’s Army Record at the Gloucestershire Archives, Gloucester. Viewed on line 5/12/2017.

3. Trethowan HW, 1981, Ivor Gurney’s Mental Illness, published in Music and Letters, Oxford Journals, Oxford University Press.

4. Cheltenham Chronicle and Gloucestershire Graphic, 1/01/1938, p2, “Death of Mr Ivor Gurney, Mind Affected by War Sufferings”.

5. Cheltenham Chronicle and Gloucestershire Graphic, 1/01/1938, p2, “Death of Mr Ivor Gurney, Mind Affected by War Sufferings”.

6. Times of London, 28/12/1937, p14, “Mr Ivor Gurney, Poet and Musician”.

7. Hurd M, 2008, The Ordeal of Ivor Gurney, pub. Faber and Faber.

Further Reading

1. The Ivor Gurney Society website at https://ivorgurney.co.uk/.

2. The Penguin Book of First World War Poetry (Penguin Classics), Edited by Matthew George Walter, 2006.

Author: David Bell.

Copyright © December 2017, LWS (UK) CIC.