Dr William Chester Minor

The biographer Simon Winchester once said that, “the story of W.C. Minor was indeed a footnote in history”1 and perhaps that observation can be made of all the famous people that we have featured in this section of the website: John Nash, Richard Dadd, Ivor Gurney and the others never really changed the world but they all of them, in their own unique way, left a robust, distinct and indelible impression on it and without a doubt the world would be a sorrier place were it not for their contributions.

Early life

Dr. William Chester Minor, taken in his later years at Broadmoor. (Image: Unknown author. From Wikimedia Commons. In the public domain)

William Chester Minor was descended from a family of well-to-do Connecticut aristocrats. In 1833 Minor’s father, Eastman Minor became a Congregationalist missionary (an evangelical protestant faith) and moved to Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) with his new bride Lucy. William, born June 22nd 1834, was their first child. We do not know a great deal about Minor’s childhood except that he lost his mother to consumption (tuberculosis) when he was just three years old. Minor was sent back to the US at age 14 and lived with his uncle Alfred in New Haven, Connecticut. At age 24 Minor went to study medicine and anatomy at Yale University, one of America’s finest institutions of higher education, whence he graduated successfully. Following graduation, Minor enlisted in the Union Army as a surgeon, the American Civil War was at that time in full spate2.

In 1864 whilst still an undergraduate, Minor was asked to work as a contributor on Webster’s new dictionary. It is true to say that he did not shine at this work and many of his entries were subject to some criticism by his peers. It did, however, give him an early taste of the kind of work that in later life he was to become famous for.2

Military service

During his time as an army surgeon, in May 1864, Minor served at the Battle of the Wilderness at Locust Grove, Virginia, an engagement that was considered particularly brutal even by the standards of the American Civil War. The casualties were great and many men were killed not only by musketry and artillery but also in a quite gruesome way by the wildfires that broke out in the undergrowth. The BBC website5 cites one quotation from a veteran of the battle: It was as though “hell itself had usurped the place of earth“. Without a doubt, as a surgeon in a field hospital Minor must have been victim to many gruesome sights.

Mental illness in US

Following his war service, Minor continued his army career. We know that in 1864 he was working at the Knight General Hospital in New Haven, Connecticut whence he published a series of detailed accounts of post mortem examinations that he had carried out26. He also worked at L’Overture Hospital in the city of Alexandria before moving to the Governor’s Island garrison where he was eventually promoted full captain in September 1866.19

However, it was not long before the first clouds of the mental turmoil that were to overshadow this promising military career began to gather. Within a few years Minor’s bizarre behaviour began to cause concern amongst his army colleagues. He was working at Governor’s Island in New York Harbour and was seen to spend an excessive amount of his free time with prostitutes. Consequently, he was transferred to Fort Barrancas in Florida19. Later, after his transfer to Florida, he began accusing his colleagues of plotting and conspiring against him2. He had developed firmly entrenched beliefs that he was being persecuted by an Irish secret society.

There were also episodes of violent behaviour around this time and in one case Minor was reported to have challenged a fellow officer to a duel. In September 1868 at age 34 he was examined by army doctors who found him to be delusional, violent and homicidal and diagnosed a condition then called monomania resulting in his delusions,4, and recommending that he be admitted to the Government Hospital for the Insane in Washington DC4 (which later became St Elizabeth’s Asylum) and which he entered voluntarily2.

Simon Winchester’s book, The Professor and the Madman, gives us some useful insights into his condition at this time. A year after Minor’s admission to the asylum a team of army doctors reported, “Our observations lead us to form a very unfavourable opinion as to Dr Minor’s condition.” …..”A very long time may elapse before he can possibly be restored to health”20.

Trip to England

In the Spring of 1871 Minor was discharged from the Washington asylum 12 and at the same time was retired from the army. The doctors considered that his mental illness was rooted in his war service and he was awarded an army pension. Minor’s family suggested to him at this time that his mental health might benefit from some time spent travelling and thought that a spell painting in England would do him good. Minor was an accomplished watercolourist. One of his friends from Yale offered to put him in touch with John Ruskin the celebrated English writer and art critic.

But it is likely that Minor had another purpose in mind at the time he came to England. Police superintendent Wiliamson, who later gave evidence at Minor’s trial, said that Minor told him that he had come to England to escape the persecution that he believed he was victim to in the US13. However, poor Minor’s hopes of escaping his terrors were soon dashed. Whilst living at an hotel in Central London he once again became convinced that the Fenian secret society that had been pursuing him in America had now followed him to England. And he was intent on defending himself from them, a resolve that was to end in tragedy.

Killing of George Merrett

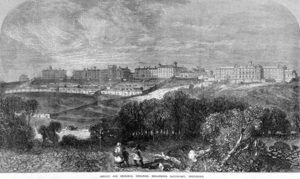

The Lion Brewery, Lambeth South London. Scene of George Merrett’s death in 1827. (Image: Unknown author. From Wikimedia Commons. In the public domain)

At about 2.00 am on Saturday 17th February 1872, a clear, starlit night with a bright moon, Minor shot Mr George Merrett (or Merritt) a brewery stoker from the Lion Brewery in the street in Lambeth, a district of London. The two men did not know each other. After shooting Merrett, Minor then attacked him with a Bowie knife that he was carrying under his jacket causing further but unnecessary injury, the gunshot wounds being already fatal10. Merrett died quickly. Minor was quickly apprehended by a patrolling police constable who disarmed him and on being questioned freely admitted to the officer that it was he who had fired the three shots6.

The police constable then sent the senseless Merret to the nearby St Thomas’ Hospital by cab in the custody of another policeman. There the casualty was examined by the house surgeon, Henry Williams and life was pronounced extinct. The surgeon found bullet wounds in his chest and neck and concluded, pending a post-mortem examination, that they were the cause of death. Merrett left a pregnant widow and seven children10.

At the Tower Street police station Minor was searched and the Bowie knife found. Some recent accounts state that Minor now told the police that he killed Merrett because he believed that he had broken into his room while he had been asleep in order to administer poison to him. However, contemporaneous press reports state that Minor offered no explanation of his actions to the police whilst in custody at the police station or prison and it is possible that these accounts arise from the testimony given by the family and police witnesses at his trial rather than Minor’s own10. Nonetheless, this particular delusion, in several slightly different variants, was to plague Dr Minor for the remainder of his life. At times he believed that the abusers were stupefying him by administering chloroform while he was asleep and then abusing him sexually. In 1877 he began to believe that he was being tortured with electricity during the night and the following year that he was being secretly removed from the asylum at night to be abused4.

Following Minor’s arrest, police officers were sent around to his lodgings to search for evidence and there they found a letter explaining that Minor had been discharged from the US Army because an attack of sunstroke had affected his ability to practice as a doctor. Other letters explained that Minor had been advised by his friends to go travelling in England as a means of possibly recovering his mind. There was also a letter of introduction to Mr John Ruskin. In the course of the day Minor was duly charged with wilful murder and appeared at the Southwark Police Court (magistrates court) for committal. The police constable arresting Dr Minor told the magistrate that when arrested there was not the slightest sign of drink on him and he did not resist arrest. The prisoner was then remanded in custody to the Horsemonger Lane Gaol10.

An inquest was convened by the Coroner, Mr Wiliam Carter on the following Monday, 19th February and also returned a finding of wilful murder11. Minor was then held in custody and committed for trial to the Surrey Assizes on the charge of wilful murder8.

Following the committal hearing a number of different explanations circulated in the local press regarding Dr Minor’s motives. One account given was that he had just been robbed by a pimp and had mistaken Merrett for him. Another explanation was that he was part of some sort of inheritance scam involving another employee of the brewery. It is likely that these stories, which were never supported by evidence, arose from the press’s quite natural desire to find some sort of rational motive for the killing and before the evidence of mental ill health became apparent to them. In any case they were not referred to at the assizes trial17.

It has also been widely put about that Dr Minor’s move from the central London hotel that he took when he arrived in England, to lodgings in the South London district of Lambeth was to facilitate more convenient access to prostitutes. This rather scurrilous suggestion does not have any basis in the press reports of the day. Scotland Yard were clear to the court that Minor had left the hotel because he feared that the staff there were in league with the Irish Fenians. Detective Williamson told the magistrate that Minor “believed that his persecutors had followed him from America and that someone in the hotel where he was staying was in league with them”12.

Trial and commitment to Broadmoor

Minor was tried at Kingston Assizes before the Lord Chief Justice, William Bovill and defended by Mr Edward Clarke on the instructions of the American Vice Consul. The Honourable G. Denman QC prosecuted assisted by Mr C.J. Mathew13. The defence admitted the facts of the killing but argued for an insanity verdict12. Evidence was heard from the arresting and investigating police officers, from the surgeon at St Thomas’ Hospital, from a gunsmith, Minor’s landlady and from Merrett’s widow13.

The defence claimed that Minor’s insanity had been caused by his experiences of warfare and particularly an episode in which, following the Battle of the Wilderness, Minor had been required to brand on the face a young Irish soldier as punishment for desertion4. It was claimed that Minor believed that this man had been a member of a secret society whose members had been pursuing him and persecuting him12. It was also stated that Minor had had a bad episode of sun stroke whilst in the army and that had been thought to be the cause of his mental illness by some doctors in the US7.

A detective Williamson from Scotland Yard testified that in the months before the killing they had had several approaches from Minor both by letter and in person in which he claimed that he was being persecuted by a conspiracy of Irishmen who were trying to poison him. He had concluded from this that Minor was suffering from delusions8. Williamson adduced in evidence a letter he had received from Minor recently in which he said:

“Sir, I was narcotised last night into a stupor from about two in the morning until after one this afternoon. I suspect this was some attempt to take my life in ways that would not be apparent – either in some such way, or by attempting to give it the colour of a suicide. My life may be taken any night…..will you assist in the matter. I shall be glad to do so. I trust your agents are not to be bought over, as American police have been by money.”13.

Wiliamson went on to say “I asked him the particulars of the persecution and he said that persons who were invisible to him came into his room in the night-time and he believed tried to poison him, and on his waking in the morning he had a burning sensation in his throat and tongue”13.

A prison warder at the remand prison at Horsemonger Lane was called to give evidence of Minor’s mental state and described how Minor would accuse him and the other guards of allowing him to be sexually abused in his cell at night4. The prison doctor, Thomas Waterworth testified that he believed that Minor was insane at the time that we was admitted to prison and still was12. And Minor’s step brother was also called to the witness box and testified that the delusions already described to the court were similar to those that Minor had suffered from whilst in America4. He told the court that his brother had complained of prowlers in his room at night when he was living with the family during 1871 and that he had been so passionate about the issue that he had insisted that he sit up with him all night to try to catch them. He had also complained of being poisoned with a metallic substance during this time12. Minor himself did not answer any questions in court and nor did he give any reason for his killing Merrett12.

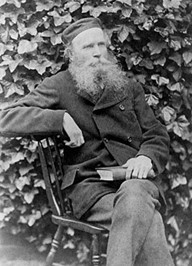

Lord Chief Justice Sir William Bovill who tried Dr. William Chester Minor for murder in 1872. (London Stereoscopic and Photographic Company on Wikimedia Commons. In the public domain)

Having heard the various witness testimonies and after a brief summing up by the Lord Chief Justice, the jury duly returned the special verdict of “not guilty by reason of insanity” and Minor was ordered to be detained “until Her Majesty’s pleasure be known”16.

Minor’s trial came almost 30 years after the famous McNaghten case had resulted in the legal code of the same name by which defendants were assessed for mental ill health when accused of a serious crime and brought before the courts for trial. However, it was an earlier instrument, the 1800 Act for the Safe Custody of Insane Persons Charged with Offences, which gave rise to what subsequently became known as the “special verdict” of “not guilty by reason of insanity” which applied in Minor’s case. This act resulted from the case of one James Hadfield who had tried to assassinate King George the Third at the Drury Lane Theatre on 15th May 18003.

Minor was thus classified as a “criminal lunatic” under the Act, a classification that affected the standard of confinement that he was to receive whilst in Broadmoor3. He was transferred to Broadmoor Asylum from the local prison on 17th April 18725. Despite the problems of bringing witnesses over the from the US to testify at his trial and obtaining the necessary expert testimony here, just two months had elapsed since the killing of George Merrett to Minor’s incarceration at Broadmoor. It appears that in the 19th century our criminal justice system displayed an efficiency and vigour that sadly cannot be matched today.

Conditions for Minor in Broadmoor

Broadmoor Asylum in Berkshire drawn in 1867. (Illustrated London News on Wikimedia Commons. In the public domain)

The Broadmoor institution is situated in the village of Crowthorne in Berkshire about 50 miles outside London. It was built in 1863 to care for both male and female patients who began arriving from 1864. Broadmoor was intended to replace the accommodation for “criminal lunatics” (as they were at the time known) which formed part of the Bethlem Asylum in South London and which was widely acknowledged to be inadequate both in terms of its size and also the facilities and environment that it provided.

Broadmoor was seen as pioneering and represented fresh thinking in the field of care for the mentally ill. No longer were the criminally insane to be merely warehoused in secure accommodation until they recovered under their own steam but now an institution was to be provided whose environment, it was hoped, would encourage a return to sanity and permit the patients to one day be reinstated into the general community. The environment was intended to be clean and wholesome with access given to the open air and useful occupation like crafts, entertainment and sports provided. And to an extent this aim was successful.

Minor was, from the start of his time in Broadmoor, considered to be a low-risk patient and accorded many privileges which were not available to other inmates. The US Consulate sent comforts such as clothes, drawing equipment and food for Minor and he also had the advantage of both a financial allowance from his family in the US and his officer’s pension from the army4. According to one of the later superintendents (director) of Broadmoor replying to an academic enquiry in 1958, Dr Patrick McGrath said that at one point Minor was given an adjacent cell to use as a day room and also allowed to employ other patients as his domestic servants4.

Minor was able to build an extensive library of antiquarian books during his time in Broadmoor and his tastes in reading, according to Simon Winchester in his book The Meaning of Everything, tended to, “the obscure, the foreign and the old”18. It is thought that this activity brought him into contact with the public appeal put out by James Murray, the lexicologist asking for volunteers to help contribute suggestions for a new publication to be called the Oxford English Dictionary.

In the 1840s a small group of intellectuals in London expressed some dissatisfaction with the existing dictionaries of the English language then available and set in train a project to produce a definitive work. The scope of the work was however very great and so during the 1870s Oxford University agreed to publish the work under the leadership of James Murray. Murray had the idea of issuing a public appeal for volunteer readers who could read widely and then refer to the dictionary staff examples of the usages of words and their contexts.

In addition to his work on the dictionary Minor was also allowed to paint and play his flute (he was accomplished in both activities).

Work on the O.E.D.

Over the following 20 years Minor worked assiduously on the O.E.D. contributions whilst at Broadmoor and was ultimately considered to be one of the major contributors to that work. He had, however, learned from his previous experiences on his work for Websters Dictionary in the US. Now he confined himself to simply finding and identifying the contributions rather than defining them. As Winchester says of him “he was a reader of books and provider of quotations not…. a critical student of the proofs”.

A quotation from Murray reproduced in an article in the Nation gives a revealing insight into the diligence and energy with which Minor approached this work2.

“The supreme position is…certainly held by Dr. W. C. Minor of Broadmoor, who during the past two years has sent in no less than 12,000 quots [sic]…. So enormous have been Dr. Minor’s contributions during the past 17 or 18 years, that we could easily illustrate the last 4 centuries from his quotations alone.”

Dr Minor was not the only volunteer contributor to the O.E.D. by any means nor the most prolific but given his undoubted handicap he was perhaps one of the most dedicated. Winchester says that his story is one of “dangerous madness, ineluctable sadness and ultimate redemption”18. “Redemption because he found in his work for the dictionary a form of therapy which made his tortured life a little more bearable perhaps”.

A romanticised account of how James Murray first met Minor has been oft repeated: how Murray visited Broadmoor to meet Minor under the misapprehension that he was a doctor employed at the institution and was therefore surprised to find that he was a patient. However, this account was rebutted at the time by Murray’s successors on the O.E.D. and it is likely that Murray was aware that Minor was a patient at Broadmoor for some time before they first met in 1891. There is, however, nothing fictional about their friendship which was very close and endured for over two decades.

Course of illness in Broadmoor

Dr Minor’s work on the Dictionary is testament to the enormously beneficial effect that useful occupation can have on people suffering with schizophrenia. And occupation was an intrinsic part of the Victorian’s thinking here. Most of the asylums built by the Victorians during that age for people with mental illness had accompanying farms and sheltered workshops attached which proved to be extremely effective in reducing symptoms. It was often observed that patients who were beset by symptoms whilst on the ward would become completely symptom-free when working out on the farm in the afternoon. It is perhaps sad that in a classic example of “throwing the baby out with the bathwater” these beneficial facilities were lost when the asylum system was abolished.

But despite his occupation on the Oxford Dictionary, Dr Minor’s mental turmoil proved to be relentless and he continued to suffer from his delusions and hallucinations throughout his stay in Broadmoor. This was the time before the advent of the effective antipsychotic medicines that we have today. These antipsychotic medicines, first discovered in the 1950s, have become the mainstay of treatment for hallucinations and delusions in schizophrenia and will provide some relief from these sorts of symptoms in about 70% of those sufferers taking them.

A look at some of Minor’s ward notes reported in Simon Winchester’s book gives us some insight into his plight:

“April 1873: ….at night he barricades the door of his room with furniture”.

“June 1875: The doctor is convinced that intruders manage to get in – from under the floor or through the windows – and that they pour poison into his mouth through a funnel”24.

Self-mutilation

Despite the undoubted fact that William Minor was able to think and act lucidly enough to carry on his voluminous and valuable work for the O.E.D., his psychotic symptoms never really abated during his time in Broadmoor. Then one night on 3rd December 1902, at the age of 68, Merrett tied a tourniquet around the base of his penis and proceeded to amputate the member using a knife that he had been allowed to keep for his literary work. He was taken to the asylum infirmary and treated and he remained there for four months. On being interrogated about this, Minor said that he had done it because he was being taken out of the asylum secretly by night and forced to fornicate with women in some numbers.

Deportation and return to US

As the 19th Century came to a close and a new century dawned, Minor’s family started to make efforts to secure his discharge from Broadmoor, a cause which the asylum authorities were sympathetic to as they were becoming increasingly concerned about his ability to look after himself within the asylum environment. His general physical health was also worsening. He suffered from a severe bout of flu at one point and also very badly scalded himself whilst bathing4.

Home Secretary Winston Churchill authorised the discharge of Dr. Minor from Broadmoor Asylum. (taken in 1911) (Bassano on Wikimedia Commons. In the public domain)

Minor’s family petitioned the Home Office for his release in 1899 but were unsuccessful. In 1903 they tried again, this time at the instigation of Dr Brayn the Broadmoor superintendent, who made the suggestion that he might be discharged to return to America. This found a more sympathetic ear in the government of the day and the then Home Secretary, Winston Churchill (whose mother was herself an American), duly issued the discharge and deportation order4. In 1910 Minor finally left England by steamship in the care of his brother bound for America. He had been confined in Broadmoor for 29 years4.

Final years and death

On his return to the US Minor was re-admitted to St Elizabeth’s asylum where he was diagnosed with dementia praecox, as schizophrenia was then called, and remained there until November 1919 when he went to live at the Retreat for the Elderly Insane at Hartford, Connecticut. There he a passed away peacefully on 26th March 1920 following a head cold that turned to pneumonia4.

Assessment of symptoms

At the time of Minor’s diagnosis with schizophrenia in the US, schizophrenia was still a relatively new diagnosis. The condition had only been described by the psychiatrist Emil Krapelin in 1893 and the term schizophrenia was not used until 1908. As the diagnosis was so new so too were the diagnostic criteria and there was a certain amount of misuse of the diagnosis in the early days. But regarding Minor’s symptoms we can be fairly certain that his condition was indeed schizophrenia.

The delusion of being persecuted by a conspiracy of individuals is well established in schizophrenia. For Mcnaghten it was the Jesuits, for Dadd it was the Austrian Emperor and the Pope, and for poor William Minor it was the Irish Fenians. A fairly large proportion of people with schizophrenia will experience paranoid delusions and often their beliefs will reflect the age and society that they are born into. In Western societies ideas around religion used to be common in psychotic thinking whereas now beliefs that the individual is being spied on by the security services, that electronic devices have been implanted in them and that the internet is being used to spy on them are more common14. The way in which William’s delusions changed over time to include nascent technologies such as electricity and airplanes is also very typical of the schizophrenic condition.

There is also an association in schizophrenia between paranoid beliefs and dangerous behaviours like suicide and violence. In this case both violence and self-harm were prominent features. It is important to acknowledge that for a person with schizophrenia experiencing paranoia the beliefs are not simply vague ideas but are fixed beliefs which dominate thinking and do not usually respond to persuasion. They are often more firmly held in the patient’s mind than any other thoughts they may have. Sufferers who believe they are being persecuted may well strike out at those they believe are responsible.

The sexual themes in Dr Minor’s delusions are also not uncommon in schizophrenia. About 8% of people with schizophrenia will engage in some form of sexually disinhibited behaviour21. Readers interested in learning more about this unique feature of schizophrenia may care to refer to the seminal Northwick Park Study of 1986 which provides some useful insights25.

Another aspect of Minor’s symptoms which is pertinent is his belief that he was being poisoned and the experiences of metallic tastes in his mouth. This was clearly a hallucination. Hallucinations can be a product of all of the senses. Although most commonly in schizophrenia we hear of auditory hallucinations (hearing voices) in fact people with schizophrenia are also vulnerable to seeing visions (visual hallucinations) as well as hallucinations of taste, smell and touch.

Interestingly, Simon Winchester’s book tells us that Dr Minor’s work for the dictionary would drop off during the summer months with fewer contributions of new words being made during this time22. This is, of course, what we would expect to see. Schizophrenia is a highly seasonal condition with both diagnoses and inpatient admissions increasing during the summer and during periods of particularly hot weather.

Experiences as a framework of psychosis not a cause

It was popular in previous times and still is in some quarters these days to see the roots of serious mental health conditions like schizophrenia as lying with previous life experiences and in Minor’s case the blame has been laid variously at the door of his previous history of lascivious thoughts about women and his horrific experiences of warfare in the Civil War5. A number of commentators have attempted to link Minor’s paranoid delusions regarding an Irish conspiracy with the branding incident at the Battle of the Wilderness but the reality is not that straightforward.

The hypothesis that previous experiences of trauma can cause schizophrenia to develop in later life is a highly contentious one. Much hard research was done on this issue in the latter part of the 20th Century and the consensus that developed was that previous life experiences do not cause (although they may trigger) schizophrenia but that the causes are rooted in other issues, most prominently genetics but also issues such as the age of father, migrant status, urban upbringing birth season, infection during pregnancy, and trauma during birth amongst others. It is significant that Minor’s family had a background of serious mental ill health with two of his relatives dying by their own hand23.

Besides, the epidemiology simply doesn’t support the theory. If trauma in early life were to cause schizophrenia later on then we would have expected to see epidemics of schizophrenia occurring following major societal traumas such as the Holocaust or major wars but in practice such epidemics have never been observed. The incidence of schizophrenia appears to be remarkably stable over both geography and time.

However, it is certainly the case that all of a person’s past experiences, thoughts and ideas form the framework for the psychotic beliefs that develop during a schizophrenic illness. And this has certainly been observed to be the case. It is a quite straightforward and logical position that the brain, on descending into a psychotic haze, will reach for and find all the contents of the memory and will then use those experiences as the structure on which to hang all of the new psychotic thinking9.

Conclusion

Like the other Victorians with schizophrenia that we have covered in this section of the website, Minor’s story is firmly one of what may have been. For had Dr Minor been born a century later he would have had the benefit of the modern antipsychotic medicines that have brought much needed relief to many thousands of sufferers of this cruel and enigmatic condition that we now call schizophrenia. We must of course not allow our understandable sympathy for Minor to cloud the grievous tragedy of the loss of poor George Merrett but it is important that we also learn to blame the illness rather than the person for these catastrophes. Schizophrenia is a unique condition in this important respect: that an episode of schizophrenia will all too often create a whole penumbra of victims around the central one who is of course the sufferer himself.

Footnote

A film of the story of Dr Minor is now available on DVD starring Mel Gibson and Sean Penn15.

References

1. Lecture given by Simon Winchester at Anne Arbor, University of Michigan, published on You Tube and viewed 9th November 2021.

2. Kendall J, A Minor Exception, published in The Nation 4th April 2011 and viewed on line 8th November 2021.

3. Allderidge P, Criminal Insanity: Bethlem to Broadmoor, published in the Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine, September 1974.

4. Broadmoor Revealed: Some Patient Stories, Berkshire Record Office 2009.

5. Broadmoor’s Wordfinder, BBC Website viewed 9th November 2021 at https://www.bbc.co.uk/legacies/myths_legends/england/berkshire/article_1.shtml

6. Great Britain, Special Despatch, Frightful Murder in Lambeth, South London Chronicle, 24th February 1872.

7. Chicago Tribune 6th March 1872, Mary Evans Picture Library.

8. Untitled Cutting, The Graphic, 2nd March 1872, Mary Evans Picture Library.

9. Author’s personal experiences.

10. Murder in Lambeth, Evening Mail 19th February 1872.

11. The Lambeth Murder, The Mail, 21st February 1872.

12. The Lambeth Murder, The Globe 5th April 1872.

13. Spring Assizes, Murder by an American, The Morning Advertiser 5th April 1872.

14. Torrey E, 2013 Surviving Schizophrenia, Harper Perennial, p27.

15. The Professor and the Madman, 2019, DVD, Farhad Safinia, viewed 9th November 2021.

16. The Belvedere Road Murder, South London Chronicle, 6th April 1872.

17. Extraordinary Murder in London, North London News, 24th February 1872.

18. Winchester S, 2003, The Meaning of Everything, Oxford University Press, p194-201.

19. Winchester S, 1998, The Professor and the Madman, Harper Perennial. P68.

20. Winchester S, 1998, The Professor and the Madman, Harper Perennial. P71.

21. Rollin H, 1980, Coping with Schizophrenia, Burnett Books. P 23.

22. Winchester S, 1998, The Professor and the Madman, Harper Perennial. P159.

23. Winchester S, 1998, The Professor and the Madman, Harper Perennial. P183.

24. Winchester S, 1998, The Professor and the Madman, Harper Perennial. P124.

25. Johnstone E et al, 1986, The Northwick Park Study of First Episodes of Schizophrenia, Published in British Journal of Psychiatry.

26. Post mortem examinations made at Knight USA General Hospital by A.A. Surgeon W.C. Minor, 1864, In the Welcome Collection.

Author; David Bell.

Copyright © November 2021 LWS (UK) CIC.