Cognitive Symptoms of Schizophrenia

In other information sheets we have discussed the two major types of symptoms traditionally thought to characterise schizophrenia: first of all the positive symptoms such as delusions like paranoia and the hallucinations like hearing voices and secondly the negative symptoms such as social withdrawal, lack of motivation and apathy.

However in recent years it has become clear that a third category of symptoms, called by doctors: cognitive symptoms also appear. Cognitive symptoms involve problems with concentration and memory and can be just as disabling as the other types of symptoms. Because schizophrenia has these different types of symptoms it is known as a multilateral condition.

The cognitive symptoms can be summarised as:

· Impaired higher or ‘executive’ functioning (being capable to take in, retain, interpret information then use this to carry out a task or function).

· Impairment of short term working memory

· Attention deficit

· Dementia

The onset of these symptoms is usually realised in the same way as negative symptoms in that they only begin to be noticeable after the dominance of psychotic episodes or positive symptoms have either been controlled with medication or diminished with age.

The first noticeable effect of cognitive impairments can be gradual and subtle such as the decline in ability to engage in intellectual or higher activities, once formerly performed as a means of entertainment. For example, reading for pleasure especially fiction or watching drama on television. There have been extreme cases where a person stares blankly at the pages of a book that unbeknownst to them, is upside down or sitting in front of the television but looking vacantly to one side of it.

Similarly, the ability to receive instructions then carry them out unsupervised by the instructor can also be noticed. For example, being instructed to go into another room or area to locate an item that is described in both appearance and probable location can become difficult or nigh impossible, especially if the place is new and the object is previously unknown. This can be evidence of a decline in executive function, working memory and attention.

There can be some degree of overlap with negative symptoms and they can be mutually exacerbating or compound each other. For example the loss of verbal ability combined with attention deficit can make conversation extremely difficult to the point it is avoided. Similarly, the negative symptom of avolition (the loss of the will to do things) combined with diminished executive performance makes many domestic tasks or chores increasingly complex and again, avoided.

Dementia in schizophrenia

Emil Kraepelin, the psychiatrist who first described the condition we now call schizophrenia. (Image: Wellcome Images on Wikimedia Commons)

Although the existence of dementia/Alzheimer type symptoms in schizophrenia does not follow the same disease processes as those conditions, dementia in schizophrenia does appear to be linked to the age of onset of schizophrenia, early intervention and can be severe enough to warrant a secondary diagnosis of dementia into old age. Reviews of studies into the cognitive impairment associated with schizophrenia have shown that it must be assessed in the context of a sufferer’s entire lifespan and their cognitive function before onset of psychosis (pre-morbid), along with the person’s education and background. It was noted as far back as 1893 by Kraeplin, the psychiatrist who first described the condition of schizophrenia, that there is a progressive mental decline except in terms of memory and was termed ‘dementia praecox’ (premature dementia) because of the age of onset.

A study in 1999 showed that 30 per cent of sufferers who survived into old age cognitively declined enough to be diagnosed with dementia, however in a study in 2007 this figure was as high as 80 per cent. But some studies have found cognitive dysfunction in schizophrenia to be relatively stable and must be viewed in the context of a person’s life span and the age of onset and the manifestation of the other recognised symptoms. Post mortem evidence has also shown that sufferers with moderate to severe cognitive impairment did not have the physical changes in the brain of Alzheimers and there is no increase in risk of people with schizophrenia developing Alzheimers disease.

In conclusion, the actual disease processes involved in the cognitive decline associated with schizophrenia or indeed the illness as a whole remains a mystery and although there have been noticeable similarities in brain structure in people with schizophrenia there is still no definitive answer to the question, what is schizophrenia?

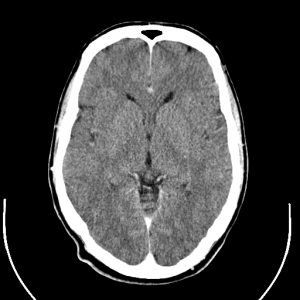

Treatments for the cognitive symptoms

Scans of the human brain using computerised tomography techniques have shown physical changes in the brains structure in many people with schizophrenia. (Image: Uppsala University Hospital on Wikimedia Commons)

Although there is no specific treatment solely for these cognitive symptoms, it has been argued that there are chemical and structural Alzheimer-type changes that take place in the brain from long term antipsychotic treatment. But it should also be noted that even in first episode unmedicated patients, certain structural abnormalities pre-exist such as a comparatively reduced brain or cerebral volume and larger than normal structures known as ventricles. Chemicals (neurotransmitters) in the brain required to connect brain cells so that certain signals can be sent and received are, among some others, dopamine and serotonin and the activity of these chemicals and the brain’s response, affect thought, emotion and feelings. For example, dopamine is a very important general basic messenger responsible for some fundamental actions and communication within and between control centres in the brain and some basic feelings.

Typical or first generation antipsychotics such as chlorpromazine or haloperidol, are blanket dopamine blockers therefore inhibiting the ability for control centres and cells in the brain to send or receive signals. As you can imagine this can have a powerful and detrimental effect on higher functions even movement. The atypical or second generation drugs such as olanzapine, are more selective in their dopamine blockade and also exert some influence on serotonin pathways in the brain. Serotonin is quite well known as the happy or love chemical but its activity and effect is much broader including anxiety, aggression and cognition. In these functions, the newer drugs act as a blocker or antagonist. In conclusion, although the positive symptoms are dealt with well by medication, the negative and cognitive ones are not as well treated.

Aripiprazole (Abilify): a new antipychotic drug that may help with cognitive symptoms. (Image: Boboque on Wikimedia Commons)

There is one possible hope, the newest drug, called aripiprazole which, instead of blocking receptors, is what is known as a ‘partial agonist’ thus stimulating certain receptors and increasing activity.

Also, although not yet licensed for the use in schizophrenia, stimulants such as dexamphetamine (Adderal) and methylphenidate (Ritalin) appear to reverse negative and cognitive symptoms as they increase the levels of dopamine in the brain however too much dopamine for too long can lead to stimulant psychosis.

Self Help for Cognitive Symptoms

In our information sheet on Treatments for Negative Symptoms we made the point that because there is not the same range of really effective medications for negative symptoms as there is for the positive symptoms that self-help is really important for people with these experiences and the same is very true of the cognitive symptoms.

Flexing your intellectual muscles will help combat cognitive symptoms. (Image: ArtFamily on Shutterstock)

It is important to flex your intellectual muscle to stimulate positive feedback activity in the brain in an attempt to maintain active pathways in the brain. This may become only possible with topics or activities that one is and always has been, fascinated with and find easy to absorb. Everyone has their subject or area such as theoretical study and expression such as a particular period of history, astronomy or quantum physics! Others may be intellectually stimulated by study of something that has a practical application like a hobby such as horses and riding or cookery.

This is also good practice to maintain good mental health and intellectual dominance over other, even negative functions of the brain to prevent a psychotic relapse and being emotionally overwhelmed and consumed as you will be in a position to cognitively challenge any paranoid delusions or voices and keep insight so that one can seek help if necessary.

Many thanks to Rob Foster who contributed this Information Sheet

References

1. The neuropathology of schizophrenia- A critical review of the data and their interpretation, Paul J. Harrison (1999)

2. Dementia in schizophrenia- Raghavakurup Radhakrishnan, Robert Butler, Laura Head, Advances in Psychiatric Treatment (Mar 2012)

3. How should DSM-V criteria for schizophrenia include cognitive impairment?- Keefe RSE, Fenton WS (2007) Schizophrenia Bulletin 33.

4. Neurocognitive deficits in schizophrenia: a quantitative review of the evidence Heinrichs RW, Zalkanis KK (1998)