Labelling in Schizophrenia

For a number of complex reasons the condition of schizophrenia probably attracts more negative associations than any other health condition. We tend to call this negative overview of the illness, stigma. There is much discussion in the mental health field around the importance of stigma with some arguing that the effect of the stigma is often worse than the effects of the illness itself and others arguing that it is the primary effects of the symptoms that are most important.

Associated with the stigma that people with schizophrenia face is what some see as the problem of labelling: that the very act of giving someone a diagnosis of schizophrenia can itself cause them problems. Below we discuss some of the arguments for and against labelling.

A Brief History of Labelling Theory

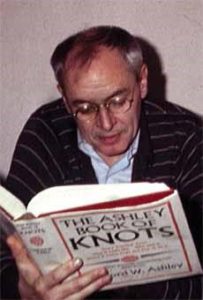

British psychoanalyst R.D. Laing who became the doyen of the anti-psychiatry movement of the 1960’s. (Image: Robert E. Haraldsen from Wikimedia Commons)

In the 1960s the anti-psychiatry movement came up with the theory that by giving someone a diagnosis of schizophrenia we were labelling them with that role and that it was the label that caused the problems rather than the illness itself. It is notable that none of the proponents of this theory had ever had to spend any time living with persecutory voices or they may have formed a different view. It is worth noting that one of the strongest supporters of the theory in the UK, prominent psychoanalyst and doyen of the anti-psychiatry movement R.D. Laing became increasingly disillusioned with it in his later years when his own daughter began suffering with schizophrenia.

The most assertive supporters of labelling theory argued that the person with schizophrenia wasn’t ill at all but simply displaying disturbed behaviour on which it was convenient to hang the label of schizophrenia. In this way it became the doctors and particularly the person’s family who were the problem not the illness. These people refused to acknowledge the terrible suffering that the symptoms of schizophrenia can cause. 1

Thomas Scheff an American sociologist wrote a seminal work on labelling theory called, Being Mentally Ill: A Sociological Theory, which argued that once a person received a label of mental illness their illness became their career and they would then start to conform to the accepted norms of being mentally ill in their society and their immediate circle of friends.2

This argument is not without foundation. Most people with schizophrenia tend to associate with others in the same boat and lacking any role models that they can draw on if they want to move on and recover they will conform with the social mores of their group. For instance if they want to look for work they may not have any friends who work and who can give them advice about practical issues such as what to say about their diagnosis at a job interview. This constraint will become a serious drawback later.

Contrast this with the situation of someone with schizophrenia in the developing world who will still be required by their community to play their part in the basic tasks of living for instance in subsistence agriculture and simply may not be allowed to adopt the role of a permanent invalid. This may be one reason why rates of recovery from schizophrenia are better in the third world than in developed countries.

Not all of the supporters of labelling theory entertained such extreme views however, there were others who simply believed that the stigma caused by the label was at least as bad and probably worse than the illness.

But whilst the sociologists took the view that all labels of schizophrenia were bad some psychiatrists were looking at it in more detail. Professor Joseph Zubin for instance concluded that the principal effect of stigma was to exacerbate the negative symptoms such as apathy and social withdrawal.3 There may be something in this as it would appear to be a natural reaction to stigma to simply try to avoid unnecessary contact with an outside world that is perceived by the sufferer as hostile and unforgiving.

Labelling Today

The belief that labelling is as harmful as the illness itself has sadly lingered on and many working in mental health today, particularly in the third sector organisations such as the mental health charities, still believe that labelling has this effect. Indeed in recent years there has been a slight resurgence in this movement and there have been some publicly funded projects set up which seek to divert young people away from the mental health system before they become “stigmatised” by their label. A theory that is as reckless as it is inhumane. To suggest that denying a seriously ill person access to the health care that they desperately need would be the most therapeutic option for them is a theory that would never gain credence in any other medical discipline.

Although labelling theory no longer has the prominence that it had in the 20th century, fears of labelling also still exist amongst some mental health professionals and sometimes diagnoses are delayed as a result. As a consequence the person who is ill is sometimes denied access to health care in a unique way that would not come into play in any physical condition.4

Allied to the belief that a label of schizophrenia is a bad thing for the sufferer is doubt over the integrity of the schizophrenia diagnosis itself. Supporters of labelling theory also maintain that the diagnosis of schizophrenia is itself a very loose association of so many features that it has become a catch all diagnosis for any nebulous mental health problems. This is another erroneous belief and is simply not the case today. The diagnosis of schizophrenia has been refined over decades of research and practical case work and we are now able to definitely associate certain psychological features e.g. hearing voices and paranoid delusions with the condition that we call schizophrenia.

Going Beyond Labelling Theory

Most people with schizophrenia will agree though that the impact of the symptoms on their lives has been devastating and that it is the effects of the symptoms rather than the stigma associated with the diagnosis that has had the most influence on their life. Furthermore labelling theory does not make allowance for the natural resilience of schizophrenia sufferers in being able to offset the effects of the stigma by their own efforts.2

There are some people who are quite happy to describe themselves as “a schizophrenic” although there are many who would object to this. But for some, being able to attach a label to their problems and to be able to finally explain all of their bizarre and distressing experiences is both liberating and empowering. It is often a breakthrough and becomes the starting point of their recovery. Some will say that mental health practitioners are often too ready to label strange behaviour as mental illness and perhaps some are. We should certainly not attempt to pathologise simple differentness. But perhaps what we should be kicking against here is not the attaching of a label of schizophrenia but the enormous social stigma that is associated with that label and that is a battle that must be fought in public opinion and particularly in the media.

But the principal problem with labelling theory is that it has succeeded in depriving so many people with schizophrenia of the health care that they need and are entitled to. It is important for workers in the mental health field, be they consultant psychiatrist or social worker, to remember that access to high quality health care is not a privilege to be bestowed by a beneficent society, it is a basic right and in the case of someone suffering from the terrifying symptoms that schizophrenia entails that access should not be impeded by unproven theories no matter how seductive they may be. It is not the diagnosis of schizophrenia that causes a thousand people with schizophrenia to take their own life each year in the UK, it is the symptoms of the illness itself and it is treating those symptoms that must be uppermost in our philosophy of care.

Unwanted Labels

However it has to be said that not all sufferers would agree with this. A complicating factor here is that some sufferers (admittedly a minority, albeit a highly vocal one) will see their schizophrenia experiences as beneficial to their life and will find any attempt to define them as an illness as disempowering and dehumanising. It is of course necessary for the person with schizophrenia to have a degree of insight into their condition if they are to properly engage with treatment and be able to start on a recovery path, however it is also necessary for the person to have a sense of empowerment over their condition: that is a self acknowledgement that they can actually succeed in life and not just survive their schizophrenia.2 In the author’s personal experience of the mental health system it is imparting this sense of empowerment on which we still have a long way to go. .

Perhaps those sufferers who are unwilling to accept a label of schizophrenia would feel more confident with the diagnosis if our health and social care systems were better equipped to give them the support that they need to make progress with their lives and return to mainstream society. Although over the past 50 years we have made some real progress in the UK in improving the medical outcomes for people with schizophrenia, the social outcomes, that ability to get back into the mainstream, has been badly neglected.

Some Labels That Really Must Go (and the Sooner the Better)

Whilst the label of schizophrenia is one that we may well have to get used to, there are other labels commonly used by mental health workers which have no place in a system of compassionate health care. Labels such as “attention-seeking”, “manipulative “ and “demanding”. It does seem that these labels are very readily attached to people suffering from schizophrenia but we may ask why should a person with schizophrenia not seek attention? They are after all suffering from a terrifying, life threatening illness and they need all the help they can get. A doctor who labelled a cancer patient or a victim of abuse as “attention-seeking” would soon find themselves in very hot water so why do people with schizophrenia suffer from this abusive labelling?

Such labels also imply choice: they suggest that the ill person is choosing to be “difficult”.5 One of the first things to understand about schizophrenia is that it strips the person of the basic human capacity of freedom of thought and within that context any notion of choice is meaningless. Someone with schizophrenia would no more choose their persecutory voices or terrifying paranoid delusions than they would choose to put their hand in the fire. It is essential that care givers and mental health workers understand that.

So perhaps there is a little more to this issue of labelling than is at first obvious. Perhaps labelling is not quite the bogey man that the anti-psychiatrists would have us believe. But whatever view you take on that, it is clear that this issue will have implications for people living with schizophrenia for the better part of their life and will probably influence their life choices for some considerable time after they are diagnosed.

References

1. Howe G, 1991, The Reality of Schizophrenia, Faber and Faber. p 82.

2. Warner R, 2000, the Environment of Schizophrenia, Brunner Routledge, p93.

3. Watkins J, Living with Schizophrenia, p28.

4. Howe G, 1995, Working with Schizophrenia, Jessica Kingsley Publishers, p11.

5. Howe G, 1995, Working with Schizophrenia, Jessica Kingsley Publishers, p54.

Copyright © January 2016 LWS (UK) CIC.