Schizophrenia: A Brief History

Early references to schizophrenia

Schizophrenia has been around for a long time. References to people who are clearly insane appear in classical writings and the bible, for instance in Mark 5 we hear of the Gerasene Demoniac who, “All day and all night among the tombs and in the mountains he would howl and gash himself with stones”. In fact the oldest recorded description of an illness like schizophrenia dates back to the Ebers Papyrus of 1550BC from Egypt.1

Descriptions of episodes of madness involving hearing voices, seeing visions and erratic and unruly behaviour start to appear in the literature from the 17th century. It is interesting to note that even then madness was seen as a medical problem rather than some possession by evil spirits although they were denied the effective remedies that we have today.7

First Breakthroughs

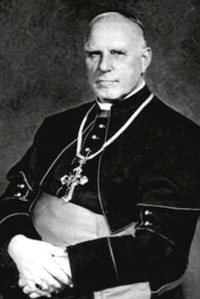

Dr Emil Kraepelin who first described schizophrenia in 1896.

Schizophrenia was first described by Dr Emil Krapelin in the 19th century. He was director of the psychiatric clinic at the university in Estonia. He first used the term Dementia Praecox or premature dementia and he believed that the condition always had a steadily worsening course or if there was any improvement over time it would only be partial.

Although Krapelin’s understanding of schizophrenia was still incomplete his work was pioneering in the way that he distinguished the condition from the other psychotic disorders such as bipolar disorder.5

Swiss psychiatrist Eugen Bleuler who first used the term schizophrenia in 1911.

Later Eugen Bleuler developed Krapelin’s ideas on the diagnosis of the condition and first used the term schizophrenia. Significantly he believed that patients did indeed show a distinct improvement over time.

The Victorian Asylums

Before the building of the Victorian asylums there was only one hospital for people with mental illness in the UK: the Bethlem. Others suffering from both mental illnesses and disabilities were usually cared for by their families or often housed in one of the work houses run by the parish for the relief of the destitute.

The enlightened leaders of the Victorian age on both sides of the Atlantic built large institutional asylums into which people with schizophrenia were confined often for many years and sometimes for life. Although some of these asylums were later exposed as abusive, at the time they were built, they were seen as a compassionate alternative to confining lunatics in prison or to life on the streets where they were prey to those criminals who would seek to exploit them.

The County Asylums Act of 1808 enabled the building of the new asylums but at first progress was slow. However by 1900 about 70 asylums had been built and were housing over 74,000 patients. The next 30 years saw a further modest increase in the number of institutions to around 90 hospitals but a doubling of the asylum population to almost 150,000.9

Control and management of the county asylums was in the hands of local authorities until 1949 when they passed into the care of the nascent National Health Service.

Early treatments, such as they were, left a lot to be desired. Brain surgery and electric shock treatment were both common and controversial but until the advent of the antipsychotic drugs were all we had. Confinement was all that could be done for people with disturbed, socially unacceptable behaviour and this was supported by using large doses of sedative drugs. This earned the name “the chemical cosh”

The old Victorian asylums like this one at Moorhaven on the edge of Dartmoor provided many people with schizophrenia with a sanctuary from the pressures of the world. (Image: Guy Wareham)

Sometimes these institutions were genuine places of sanctuary from the stresses of the world and benefited from compassionate and progressive leadership and provided a caring environment where people with schizophrenia could do well. Sadly, other institutions were less progressive where people with mental illness endured years of abusive treatment at the hands of sadistic staff.

Apart from the abuses that occurred in a small number of these institutions, one of the major criticisms of the system was seen as the “institutionalisation” of the patients. That is that very large numbers of those confined in the asylum became so dependent on the institution providing for them that they could not cope in the outside world and so could not be discharged even though their condition had long since improved.

Schizophrenia and the Third Reich

The Third Reich represents one of the most significant challenges for schizophrenia sufferers in the history of the condition not simply because thousands of people with schizophrenia died as a result but also because this tragic episode in modern European history points up the constant threat that people living with schizophrenia face from the followers of eugenics.

Faced with the seemingly intractable problem of an incurable condition that led to disturbed behaviour, in the 1930s the Nazi regime in Germany embarked on an ambitious programme to eradicate schizophrenia from the race by the use of euthanasia.

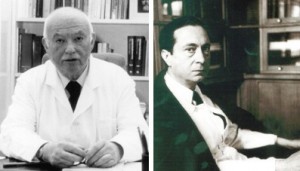

German Archbishop Von Galen who publicly condemned the Nazis programme of killing disabled people.

Although we may now see such a policy as outrageous, it had its origins in the very powerful eugenics movement which had captured the imaginations of many people across the world and was supported by many prominent people (including in the UK by Marie Stopes and Winston Churchill). In fact forced sterilisation of people with mental illness had already been introduced in a number of other countries before the Nazis got hold of the idea.

The system in Germany involved people diagnosed with schizophrenia being assessed by three approved doctors and if two agreed the person was sent to be killed. Initially this was carried out by means of lethal injection but later gas chambers were introduced as a more efficient method.

The whole programme was overseen by an organisation which went under the amazingly euphemistic title of the Charitable Foundation for Curative and Institutional Care. (It seems that then as now eugenicists love to use humane rhetoric to cloak the killing of the disabled).

German doctor Karl Brandt one of the senior figures responsible for organising the Third Reich’s euthanasia programme in which people with schizophrenia were killed by lethal injection stands trial at Nuremberg in 1946. (Image: US Government)

This practice was widely known about in Germany at the time and attracted considerable opposition particularly from religious leaders both Roman Catholic and Lutheran. In 1941 the Roman Catholic prelate, Archbishop Galen, condemned the euthanasia programme publicly in a text that was read out from every pulpit in Germany. As a result the Nazis pulled the plug on the euthanasia programme. However the respite was only temporary and six months later the programme was reinstated with renewed vigour ultimately claiming the lives of over a quarter of a million disabled and mentally ill people before the end of the second world war brought the programme to its close.

Antipsychotic medication: a new dawn

In the middle of the 20th century scientists developing new types of antihistamine drugs found that the new drugs were also effective in controlling the psychotic symptoms of schizophrenia. This was the first generation of the new antipsychotics or neuroleptic drugs called typical antipsychotics.

This breakthrough began when, in the early 1950’s, a French naval surgeon called Laboret experimented with a new drug called chlorpromazine to help with post-operative shock in his patients. He noted the effect the drug had in relaxing his patients and wondered if it could be used beneficially in psychiatry. This was the first of the new drugs that were to become known as the antipsychotics.2

Jeanne Delay and Pierre Deniker: psychiatrists at the Sainte-Anne mental hospital in Paris, who first used the new antipsychotic drug chlorpromazine in psychiatry to treat schizophrenia.

Then in 1952 two French psychiatrists, Jean Delay and Paul Deniker tried prescribing chlorpromazine for schizophrenia and found that it had a calming effect on their patients that was significantly different from the effects of the tranquillisers that had been widely used before for this condition. Rather than simply blunting the effect of the hallucinations this drug did actually seem to reduce the symptoms altogether.3

Chlorpromazine was the first of the new antipsychotic medicines (the typicals) which were able to relieve the positive symptoms of schizophrenia such as delusions and halucinations.

Unfortunately, the news that at last a treatment for schizophrenia was available was not taken up readily by the medical community since so many “cures” had been advocated over the years which subsequently proved to be ineffective. However over time the benefits of chlorpromazine and its successors were accepted.

Whilst they were good at controlling symptoms, the first generation of antipsychotics such as chlorpromazine, haloperidol and flupenthixol were not without their problems and tended to cause more problems with side effects than the more modern ones.

The early drugs had profound sedating effects and could cause tremors in the arms and legs similar to those caused by Parkinsons disease along with other physical side effects. These effects were known as extra-pyrimidal symptoms by psychiatrists. Fortunately the tremors responded well to some of the anti-Parkinsons drugs available at the time but the sedating effect had no easy remedy and led to a considerable reduction in the quality of life for many sufferers.

The beneficial humanitarian effect of the antipsychotic drugs should not be underestimated. Before the introduction of these drugs in the UK about 70% of people with a diagnosis of schizophrenia were continuously confined in mental hospitals often for years at a time: today it is only about 5% and the average length of stay in hospital is measured in months.8

Risperidone, one of the new generation of atypical antipsychotics introduced in the 1980’s and which have less side effects than their predecessors.

In the latter part of the 20th century a second generation of antipsychotic drugs called atypicals were developed. These were just as effective at controlling the psychotic symptoms (indeed in some cases better) but they had fewer adverse side effects. In addition some of these atypicals were also claimed to have a beneficial effect on the negative symptoms of schizophrenia such as lethargy and apathy.

Care in the Community

With the development of the new anti-psychotic drugs, which were effective at controlling the positive symptoms of the illness, the concept of care in the community which had already been born in the USA evolved at a pace. The new practice would involve people being looked after in their own homes rather than in hospital, with hospital stays being reserved for people in crisis.

It has to be said that care in the community got off to a very shaky start. As long term residents of the old asylums were re-located to seedy bedsits or down-at-heel bed and breakfast establishments without the support they had enjoyed in the hospital many asked if we had done the right thing in embracing care in the community.

But over time the new concept did seem to come right and despite the many problems which modern treatment methods throw up we do seem to have moved toward a more compassionate form of caring for people with serious mental ill health and the old problems of institutionalisation and abusive care staff seem now far behind us.

Although we see the policy of Care in the Community as being a product of the 1960’s and 1970’s, in fact the seeds had been sown much earlier in both the UK and US. During the second world war in the US, conscientious objectors (those who refused to be conscripted into the armed forces because of their pacifist beliefs) would be sent to work in mental institutions as an alternative to military service. They were generally horrified by what they found: the institutional system in the US had long been neglected and was in dire need of reform.

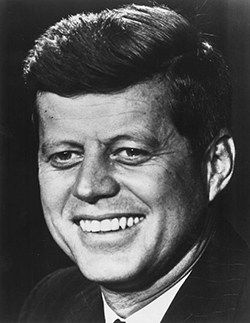

American president John F Kennedy whose sister had suffered from serious mental illness and whose government gave the impetus to the care in the community policy in the USA.

Many of the conscientious objectors were idealistic, articulate and well connected and coming from Quaker or Methodist backgrounds were acutely aware of social justice issues. They started to actively campaign for reform of the institution system.

With the election of John F Kennedy (whose younger sister had experienced mental illness) in 1960 the federal government provided the funding for the move to de-institutionalisation.4 In the UK also the start of the move towards emptying the asylums can be charted to the 1950’s and drew as its inspiration the work of the American reformers..

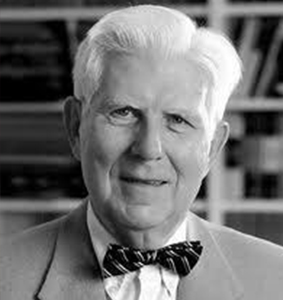

Aaron Beck the US psychologist who pioneered cognitive behavioural therapy. (Image: Bealivefr)

At about the same time that the new antipsychotics were being developed, psychologists in the USA were trying out a new form of psychotherapy called cognitive behavioural therapy or CBT which appeared to show great promise. Of course psychotherapy was nothing new: psychoanalytic therapy had been around for a long time but this new CBT appeared to be more effective in getting sufferers to take responsibility for managing their condition in a way that psychoanalysis had not. At first CBT was found to be extremely effective in treating addictions and neuroses like obsessive compulsive disorder but later it was also found to be a very useful adjunct to medication for people living with schizophrenia.

1983 Mental Health Act

In 1983 a new Mental Health Act sought to introduce fresh regulation into the way that people with serious mental illness were cared for and particularly to regulate compulsory treatment and confinement in hospital. The 1983 Act today remains the principal instrument by which people with schizophrenia are detained in hospital.

The 1983 Act also introduced new safeguards against people being wrongfully confined including an independent appeals system. Many, however argue that whilst the Act champions the rights of people with schizophrenia not to be treated or confined it does little to ensure that people who are in crisis and desperately in need of treatment for their own sake get prompt and easy access to services.6

Today

Today there are about 220,000 people being treated for schizophrenia in the UK10. Most of them do not work and most live on benefits, many in social housing. Treatment with antipsychotic medication remains the mainstay of treatment in the NHS although many do benefit from talking therapies provided by their local NHS or charities like Mind or Rethink.

Treatment is usually provided by a multi disciplinary team consisting of a consultant psychiatrist, a community psychiatric nurse and social worker support. In-patient treatment in the new generation of mental health units usually attached to the local hospital is confined to people in crisis or people whose condition may put them in danger of harming themselves or others.

Compulsory confinement and compulsory treatment usually known as “sectioning” are still tools available to the psychiatrist today under the 1983 Mental Health Act and for some patients are the best treatment options available. Whereas a full and enduring recovery requires the active participation of the patient it is still the case in this cruel illness that there will be times when the patient’s judgement becomes so distorted that treatment decisions need to be taken by their doctor or when the patient’s thinking becomes so disturbed that they become a danger to themselves or to others and have such poor insight into their condition that they remain oblivious to the risks.

In some areas additional support is provided by one of the mental health charities such as Mind or Rethink which provide centres based on the clubhouse model offering a place to meet, advocacy and advice and useful activities such as art or music therapy.

Despite the fact that most people with a diagnosis of schizophrenia do not work, the clinical outcomes for most people living with schizophrenia on modern drug regimes have never been better. About 25% of people who experience an episode of schizophrenia will fully recover and have no further problems in their lifetime. A further 25% will be substantially improved on medication whilst another 25% will be somewhat improved but will suffer from significant residual symptoms.

The final 15% will lead a chronic course involving repeated admissions to inpatient care for the remainder of their life. This leaves the remaining 10% who will die by their own hand within ten years of diagnosis: a tragically high figure which exceeds deaths from road accidents in the UK and is testimony to the neglect with which society still insists on treating this important condition.

Whilst the policy of care in the community has allowed us to leave many of the problems of the old asylums behind us there are many including this website who feel that much, much more could be done to alleviate this tragic condition.

Some argue that the Mental Health Service appears always to be the poor relation in the NHS attracting fewer resources and less publicity than other more attractive areas of NHS work such as children’s health or cancer. Some see the huge disparities in research funding between schizophrenia and other physical conditions such as heart disease as being evidence of a lack of will amongst decision makers to come to terms with the condition. Others see the very large number of people living with schizophrenia who are confined in our prisons rather than in hospital as being a lingering throwback to the old days before the Victorians built their asylums.

Whilst treatment of schizophrenia in our society has moved on there is still much to be done. For the future the challenge will be whether the attitudes of society can be changed to face up to this condition which remains one of the most serious public health issues that our society faces today.

References

1. Burton N, 2012, Living with Schizophrenia, Acheron Press, p3.

2. Howe G, 1991, The Reality of Schizophrenia, Faber and Faber, P52

3. Cutting J and Charlish A, 1995, Schizophrenia: Understanding and Coping with the Illness, Thorsons, P135.

4. Fuller Torrey E, 2001, Surviving Schizophrenia, Quill, p20.

5. Burton N, 2012, Living with Schizophrenia, Acheron Press, p3.

6. Howe G, 1991, The Reality of Schizophrenia, Faber and Faber, P52

p120.

7. Faith and Johnstone, Schizophrenia a Very Short Introduction, p30.

8. Cutting J and Charlish A, 1995, Schizophrenia: Understanding and Coping with the Illness, Thorsons, p125.

9. Leff J et al,1997, Care in the Community: Illusion or Reality, John Wiley, p5.

10. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2014, Costing statement: Psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: treatment and

management.