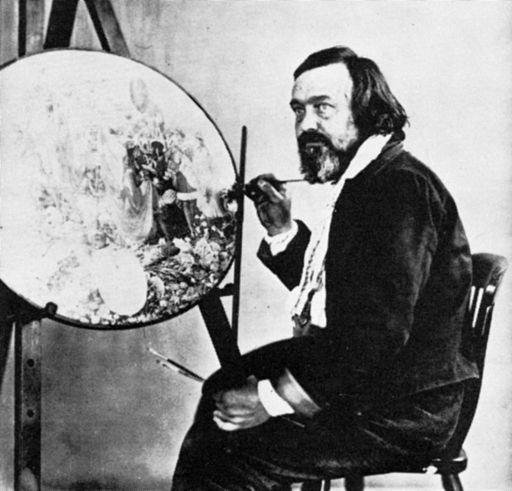

Richard Dadd

Richard Dadd (1817-1886) the famous Victorian Artist who killed his father. (Image: Henry Hering on Wikimedia Commons)

Richard Dadd was a Victorian artist who became famous during his life not only for his artworks but also for killing his father whilst in the midst of a psychotic breakdown. It is likely that he was suffering from schizophrenia at the time. His case attracted considerable public and press attention much of it surprisingly sympathetic to his plight. Although well known during his life his reputation as an artist was to decline after his death but to experience a resurgence in the latter half of the 20th century.

Born on 1st August 1817 in Chatham, Kent, Dadd was the son of Robert Dadd, a pharmacist and Mary Ann Dadd. He was to be the fourth of seven children, four of whom were to go on to suffer from serious mental illness.

Dadd’s prodigious artistic skills became apparent during adolescence and at age 17 he went to the Royal Academy of Arts in London to study. He had a precocious talent. His early work attracted great public interest and according to the art scholar Nicholas Tromans, he became the “rising star of the London art scene”7.

As is so often the case with schizophrenia, the first signs of the mental storms that were to define Dadd’s later life first made themselves felt in his mid- twenties. In July of 1843 the 26 year old Dadd was accompanying his patron, Sir Thomas Phillips on the grand tour of the middle east and whilst in Egypt began to exhibit signs of mental instability deciding to make his own way back to London. However at this stage he still retained some insight into his illness. According to Russel and Huddlestone, during this time he wrote to a friend in England: “I have lain down at night with my imagination so full of vagaries that I have really and truly doubted my own sanity”.4 On his return journey, whilst passing through Italy, he expressed a wish to seek out and attack the Pope but didn’t execute his plan.

(Image: In the public domain, from Wikimedia Commons)

Back in England Dadd’s behaviour became increasingly disturbed. His conversation became increasingly difficult to understand and he expressed bizarre beliefs. His diet became unusual and he lived for some time on nothing but ale and eggs. As is so often the case then as now it was Dadd’s immediate family who first noticed his mental turmoil and arranged for him to be seen by a doctor in London. Dr Alexander Sutherland found that Dadd was suffering from “such an aberration of the intellect” that he should be confined in an asylum. However his father disagreed with this finding and, drawing on his own medical knowledge, (he had previously been a pharmacist) felt that “quiet and retirement” was all that was needed.2

The father’s understandable compassion for his son and his wish to avoid him being confined in a mental hospital was however to prove fatal. On 28th August 1843 Dadd kept a pre-arranged meeting with his father at an inn in Cobham, Kent. Following their meal they went for a walk in the local park and whilst there Richard Dadd killed his father by stabbing him and slashing his throat.

Following the killing Dadd fled to Dover where he took the ferry to Calais in France using a passport that he had obtained few days earlier from the French ambassador in London.2

Two days after his arrival in France, travelling from Calais to Paris by carriage, Dadd then attacked a fellow passenger, again with a razor. He was arrested and disclosed to the French police his identity and that he was a wanted man in England. He was detained in the Clermont de L’Oise asylum at Fontainbleau where he remained for some ten months until arrangements were made for his extradition to England.

According to Beveridge, in France Dadd was found to have in his possession a list of other prominent people “who had to die” and was on his way to assassinate the Emperor of Austria, Ferdinand I at the time of this second attack. He told the doctors at the asylum that he had attacked his fellow passenger because he had received a message from the stars commanding him to do so.5 He also told them that he had killed his father because he believed that he had received instructions from the ancient Egyptian God Osiris to do so as his father was possessed by demons and in any case was an imposter. He also said that he saw “black devils” crawling over him and particularly in his saliva.

In France Dadd was treated by a young but very able doctor, Eugene-Joseph Woillez who, according to Helen Klemenz, diagnosed him with “homicidal monomania”6 brought on by emotional trauma, sleep deprivation and sunstroke. (It was common then as it is today in some quarters to ascribe serious mental illness to emotional trauma. However we now know that, although conditions like schizophrenia can be triggered, by such events that their root causes lie predominantly in other factors such as genetics (as was clearly the case with Dadd), the age of the father and complications during pregnancy and birth amongst others.)

Although during his later incarcerations in England Dadd was to keep painting there is no record of him having painted at all during his stay at the Clermont asylum

In 1844 Dadd was returned to England to stand trial for the murder of his father. In his committal proceedings at the Chatham Magistrates Court he was described by the reporter for the local newspaper as having a “wildness in his manner”.1 The case was committed to be heard at the next local assizes and Dadd was remanded in custody at Maidstone Jail.

Richard Dadd: The Infant Aesculapius Discovered by Shepherds on a Mountain. (Image: Creative commons attribution, from Wikimedia Commons)

It was later reported in some journals that after stabbing his father Dadd had dismembered the body. However the testimony of the local surgeon at Chatham who carried out a post mortem examination of the remains shortly after the tragedy refutes this and supports Dadd’s own claim that he killed him by a single stab wound to the chest followed by slashing his throat.

At court Dadd never stood trial, instead he became one the first people to avail themselves of the new “McNaghten rules” and was found to be insane rather than guilty of murder which would have seen him hanged. He was sentenced to be confined at the Bethlem Hospital in South London (now the site of the Imperial War Museum) where he was held for the next 20 years first in the criminal ward and then on an ordinary locked ward.

The Mcnaghten rules arose from the trial in March 1843 of Daniel McNaghten for killing Edward Drummond, the Prime Minister’s secretary, in a botched assassination attempt on the Prime Minister himself. The rules were the first attempt by the English legal system to allow a defence of insanity to a criminal offence. The court’s finding was iconic: “At the time of committing the act, the party accused was labouring under such a defect of reason, from disease of the mind, as to not know the nature and quality of the act he was doing or if he did know it, that he did not know that what he was doing was wrong”. This principle formed the basis of the insanity defence in the English legal system for the next hundred years.

Today however the insanity defence is little used in the English criminal courts, defence barristers preferring the defence of diminished responsibility instead. Whether this approach benefits the defendant or not is very debatable. It may well result in a shorter sentence but it also guarantees that the sentence will be served within the punitive prison system where the defendant is unlikely to receive the psychiatric treatment which they need and where they are undoubtedly vulnerable to the predatory attentions of their fellow inmates.

On 23rd July 1864 Dadd was transferred to the new state-of-the-art asylum built at Broadmoor near Reading in Berkshire especially for the criminally insane following the introduction of new legislation in the Criminal Lunatics Asylum Act of 1860.

As far as treatment of those with mental illness was concerned, the Victorian era was one of radical change. No longer were the lunatics to be locked up in prison to be preyed upon by the murderers and rapists but their insanity was to be properly recognised as an illness and they were to be confined in asylums: seen as places of refuge from the stresses of the outside world where it was to be hoped rest and good diet would promote recovery. Sadly, despite this enlightened approach, the Victorian doctors lacked the antipsychotic medicines that we now know to be so very effective in treating the psychotic symptoms of conditions like schizophrenia such as the delusions that were so prominent in Dadd’s case. We now know the attempts at treatment by the early doctors such as the cold baths used at the Clermont asylum had no effect whatsoever on patients with schizophrenia.

Without effective treatment Dadd’s delusions became ever more fixed and reinforced. As Boyce points out, during the whole of his time in confinement, Dadd never gained any insight into the killing of his father and his religious delusions endured throughout his time in both the Bethlem Hospital and Broadmoor. Years later he maintained that he had killed his father “in justification of the deity”.

During his time at the Bethlem Dadd continued to exhibit disturbed and combative behaviours and got a deserved reputation for attacking other patients (although he invariably apologised soon after). He was classified as dangerous throughout his time at both the Bethlem and Broadmoor but this did not stop the hospital authorities from granting him considerable freedom. He was given his own studio at Broadmoor and allowed to use knives for carvings. He was also free to access the asylum grounds where he spent many hours watching the other patients play cricket. Dadd continued to paint whilst he was confined and in addition to his artworks he also painted scenery for the entertainments hall and murals, all of which have now been lost.

The reporting in the press of the time is notable for the degree of sympathy that they extend toward Dadd. He is often described as being sad and unhappy. One piece says this “he has always been considered as a young man of a most mild disposition and had ever exhibited the warmest and most affectionate attachment to his father”2. How different this kind of reporting was to the rancorous reporting of violence by people with schizophrenia that we see in the British press today where the sufferer is demonised and their sentences often seen as excessively lenient. Reporting the insanity finding at the assizes the London Evening Standard said “No doubt can remain upon the mind of any person who witnessed the examination that the unfortunate prisoner is not morally responsible for his actions”:3 a degree of compassion and understanding that few if any journalists are willing to bring to bear in their reporting of schizophrenia today.

In his later years Dadd’s physical health declined. He contracted tuberculosis, a chronic infection of the lungs, which was commonplace at the time and he suffered from severe weight loss. In the absence of modern antibiotic drugs the doctors at the time had no cure for TB and treatment consisted of rest and diet. Dadd died on 8th January 1886 aged 68 from tuberculosis. He is buried at Broadmoor.

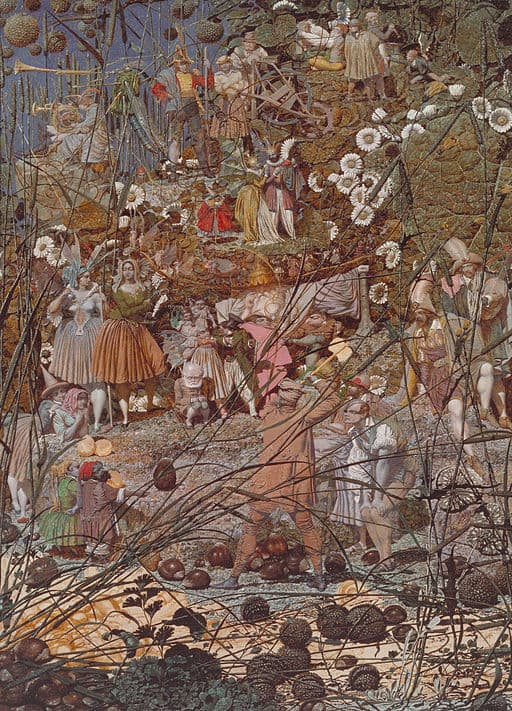

The Fairy Feller’s Master Stroke by Richard Dadd. (Image: Tate, London 2011 on Wikimedia Commons)

Despite his detailed oriental landscapes and other-wordly depictions of fairies and goblins receiving much public acclaim during his life, following his death Dadd’s artistic reputation declined and was not to be revived until the 1960s when there was a great resurgence of interest in his work. As Tromans tells us, he became seen by the nascent anti-psychiatry movement of the 1960s as a heroic survivor of psychiatry7. Perhaps they could better have seen him as the tragic victim of a particularly cruel, unforgiving and destructive mental illness for which sadly the society of the day had very few answers. The well-known pop group, Queen wrote a song about what is perhaps Dadd’s most famous work, The Fairy Fellers Master Stroke in 1973 and in 1974 the Tate Gallery in London held the first major exhibition of his work.

Dadd has been retrospectively diagnosed by some scholars as suffering from schizophrenia, a condition for which diagnostic criteria did not even exist until many years after his death. The illness of schizophrenia was not described by Kraepelin until 1899 and the term schizophrenia did not come into use until it was first applied by Eugen Bleuler in 1908. The diagnosis of homicidal monomania made at the Clermont asylum would have been appropriate to the level of knowledge that the doctors at the time had. Today we know that the kind of religious delusions that Dadd experienced are very typical of schizophrenia. In fact they are so common in schizophrenia that psychiatrists have a name for them: “religiosity”.

The age of onset for Dadd was also very typical of schizophrenia with around 75% of all diagnoses being made between ages 16 and 25. Disturbed and sometimes violent behaviour is also much more common in patients with schizophrenia than in the general population. It is highly likely that had Dadd been alive today he would have been diagnosed with schizophrenia.

Further Reading

1. A detailed appreciation of Dadd’s work is beyond the scope of this information sheet but you can see more about it on the Tate Gallery website.

2. Richard Dadd, the Artist and the Asylum, Nicholas Tromans, published by Distributed Art Publishers, 2011.

Richard Dadd the Artist and the Asylum

Reproduced with kind permission of The Tate

References

1. Kentish Gazette, 13th August 1844.

2. Kentish gazette, 19 September 1843.

3. London Evening Standard, 6th August 1844.

4. Russel G and Huddlestone S, Richard Dadd: The Patient, the Artist and the Face of Madness, Published in the Journal of the History of Neurosciences, 2015.

5. Beveridge A, Richard Dadd the Artist and the Asylum, book review published in the British Journal of Psychiatry, April 2012.

6. Klemenz H, Richard Dadd and his Demons in France, published in the Burlington Magazine, April 2010.

7. Richard Dadd: the Artist and the Asylum, published online on the Art of Psychiatry blog 18/02/2012 and viewed at http://www.artofpsychiatry.co.uk/richard-dadd-the-artist-and-the-asylum/.

Author: David Bell.

Copyright © December 2017, LWS (UK) CIC.